The RC Design Functions spreadsheet has now been updated to Version 9.03, and is available for free download from:

The new version includes a number of corrections to the calculation of beam shear and torsion capacity to AS 3600 and AS 5100.5:

- Shear capacity under negative bending moments has been corrected.

- The sign of reported shear capacity is now the same as the input shear force (previously any input with negative moment returned a negative shear capacity).

- The contribution of any negative torsion to longitudinal tension forces, to AS 3600, was taken as zero. This is actually in accordance with equation 8.2.7(3) of the code (since Amendment 2), but clearly the absolute value of the torsion should be used.

In addition, the new version allows the minimum angle of the concrete compression strut to be specified, between 29 and 50 degrees. The specified angle is used to calculate a minimum value for the mid-depth strain, which is also used in the calculation of the kv factor. Increase in the mid-depth strain value is allowed under Cl. 8.2.4.2 in both AS 3600 and AS 5100.5.

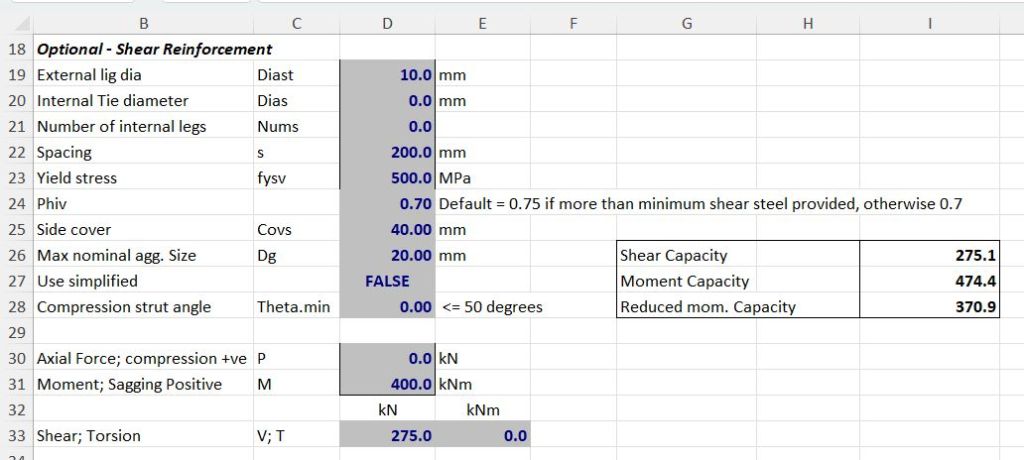

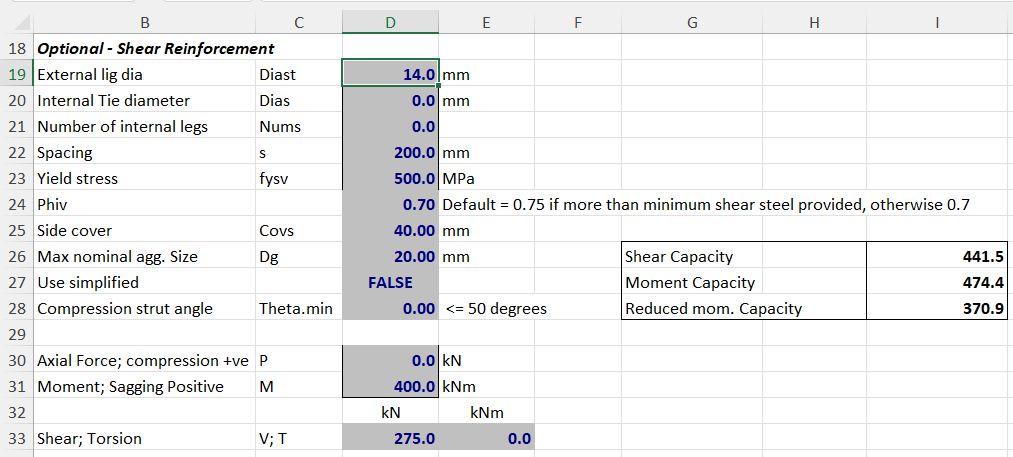

Use of the compression strut angle adjustment is shown in the screen-shots below:

A beam has design loads of 400 kNm bending moment, and 275 kN shear force. With 10 mm shear reinforcement the shear capacity is just adequate, but taking account of the longitudinal forces due to shear the bending capacity is reduced to 371 kNm:

Increasing the shear reinforcement to 14 mm diameter increases the shear capacity, but using the code calculated compression strut angle to AS 3600 the reduced bending capacity is unchanged. (Note that AS 5100.5, and earlier versions of AS 3600, have a substantial increase in the bending capacity when the shear reinforcement is increased. This is discussed further below):

Entering a compression strut angle of 49.6 degrees (with the “Use simplified” option set to “False”) reduces the shear capacity back down to the required value (275 kN), but the moment capacity is now increased to 416 kNm. Note that any further increase in the shear reinforcement would have negligible effect (to AS 3600) because the compression strut angle is already very close to the maximum value of 50 degrees:

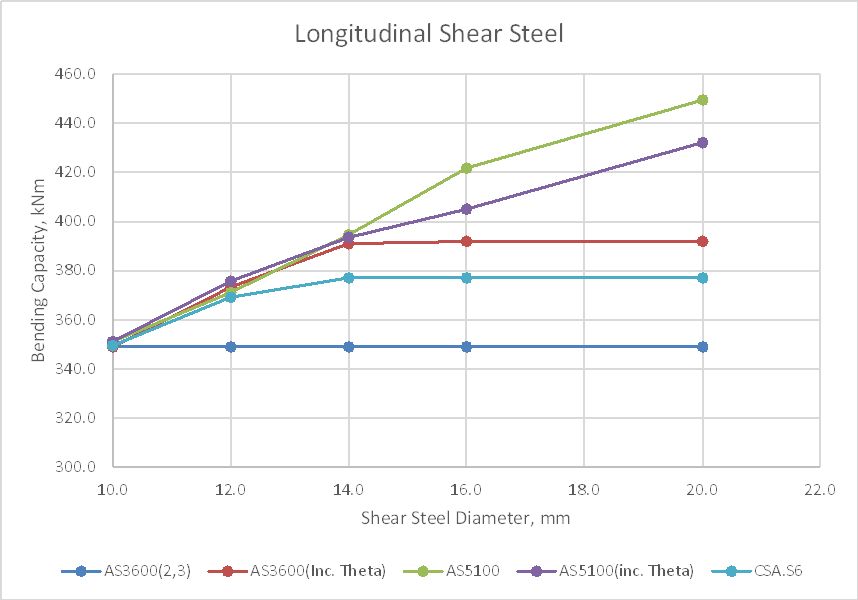

The effect of increasing the shear reinforcement on the adjusted bending capacity with different codes and approaches is shown in the graph below:

The lines are:

- 1) AS 3600, Amendment 2 or 3, default compression strut angle.

- 2) AS 3600 with compression strut adjusted to maintain constant shear capacity.

- 3) AS 5100.5, default compression strut angle.

- 4) AS 5100.5 with adjusted compression strut angle.

- 5) As 3), but shear reinforcement force limited in accordance with the Canadian Bridge Code.

So what is going on here?

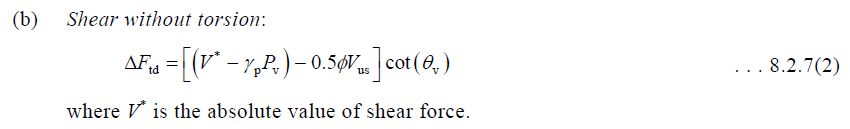

In AS 5100.5 (and AS 3600 up to Amendment 1) the longitudinal force due to shear is defined as:

Vus is proportional to the area of shear steel, and is not limited, so increasing the shear steel area allows the value of DeltaFtd to be reduced to zero, even though in reality the actual force in the steel cannot be greater than the applied shear force (V*) minus the concrete shear force. The large increase in bending capacity with increased shear steel shown by line 3) is therefore not realistic.

Increasing the compression strut angle (Thetav) with the AS5100.5 equation reduces cot(Thetav), which reduces Vus, but also reduces DeltaFtd. The resulting calculated bending capacity is still unrealistic for large areas of shear reinforcement.

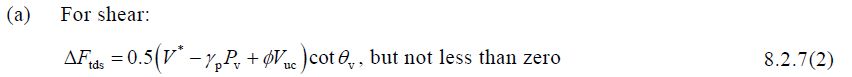

In AS 3600 Amendment 2 the equation for longitudinal force due to shear was revised to:

If the shear capacity of the section is exactly equal to V* then this equation is equivalent to the AS5100.5 version, but increasing the area of the shear reinforcement has no effect on Vuc, so there is no reduction in DeltaFtd, and the bending capacity remains constant, as seen in line 1.

In this case however increasing Thetav, which reduces cot(Thetav) reduces both Vuc and the resulting value of DeltaFtd. Increasing the shear reinforcement area therefore allows Thetav to be increased (so that the shear capacity remains equal to the design shear force), which reduces DeltaFtd, with the nett result that the bending capacity is very close to the values found from the AS 5100.5 equation, until Thetav reaches the upper limit of 50 degrees, after which the bending capacity remains constant (line 2).

Finally the Canadian Code requires the value of Phi.Vus to be limited to V*. In this case this restriction is more conservative than the approach taken in AS 3600. Bending capacities are similar to the other results for small shear reinforcement areas, but the maximum bending capacity is significantly lower than that found with AS 3600 with adjustment of the compression block angle.

In summary:

- The AS 3600 equation with default compression block angle is conservative, but shows no benefit from increased shear reinforcement area.

- Applying adjustments to the compression block angle, in accordance with the code, the AS 3600 equation gives results very close to those from AS 5100.5, up to a reasonable limit (i.e. maximum angle of 50 degrees, equivalent to a maximum mid-depth strain of 0.003).

- If the shear reinforcement area is increased well above the area required for the design shear force the AS 5100.5 equation gives bending capacity results that are highly unconservative.

- If design is required to follow the current AS 5100.5 (Amendment 1), it is recommended that the Canadian code limit (Phi.Vus < V*) be applied.