Following the the first post in this series I will move on to the py_Solvers spreadsheet included in the download file:

Details of the required pyxll package (including download, free trial, and full documentation) can be found at: pyxll

For those installing a new copy of pyxll, a 10% discount on the first year’s fees is available using the coupon code “NEWTONEXCELBACH10”.

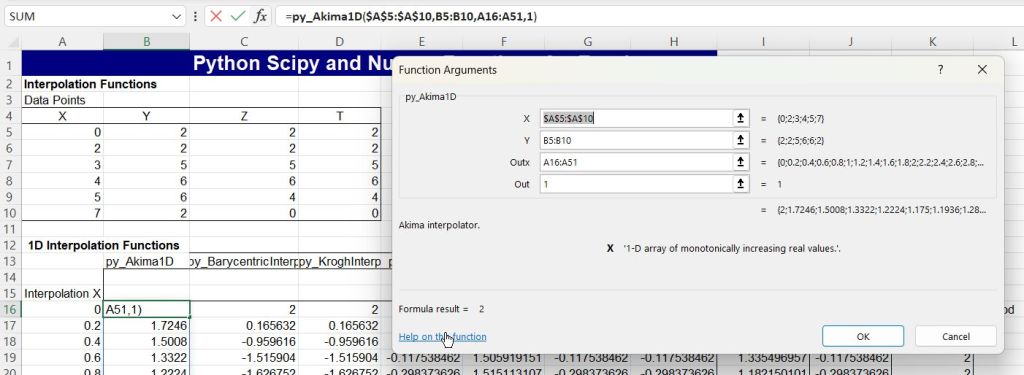

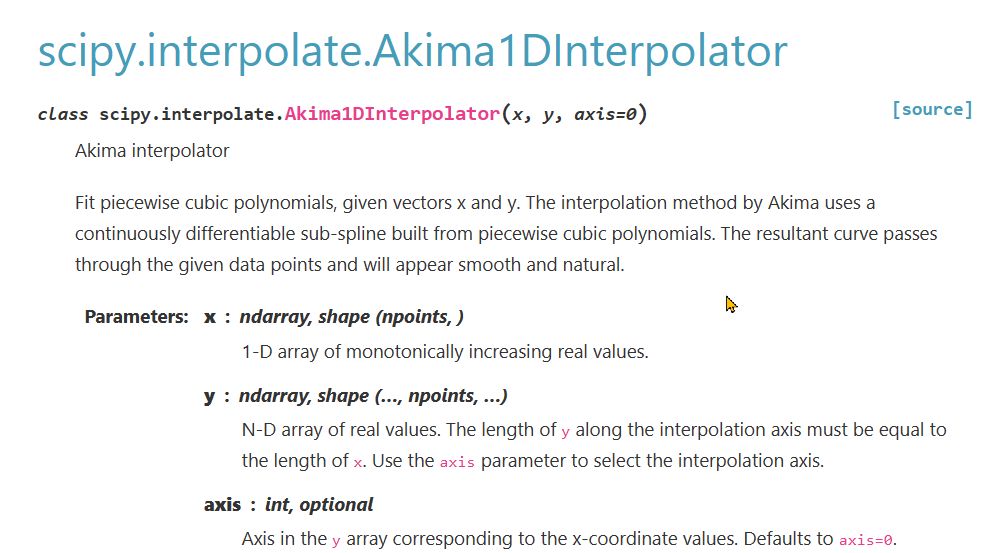

This post will look at functions for solving equations with one variable, and the next one multi-variable equations.

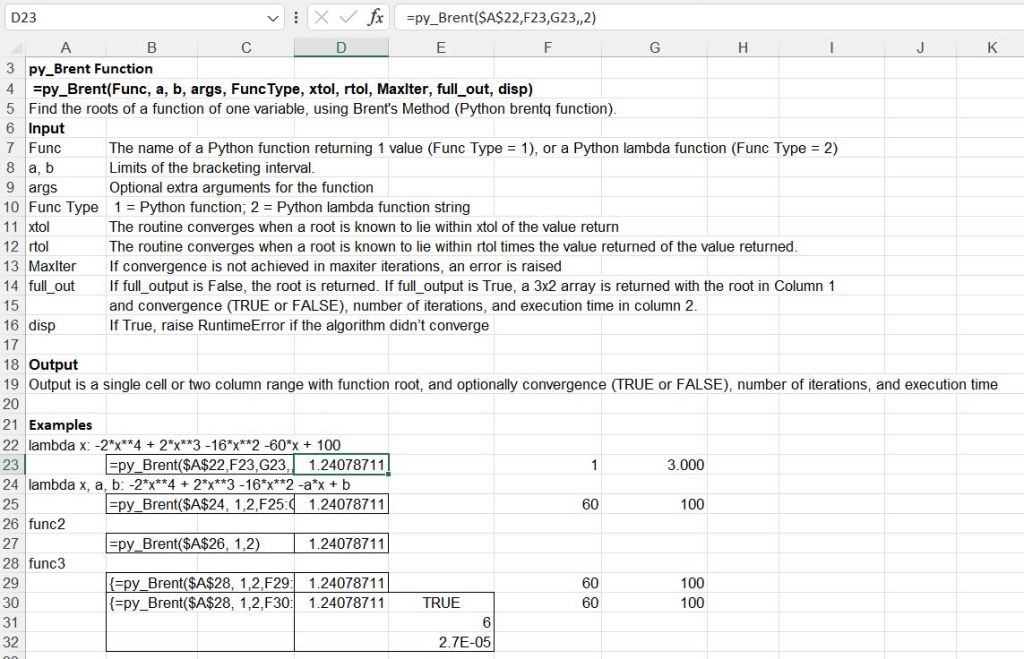

The py_Brent function finds a root to a function of one variable within a specified range using Brent’s Method:

The function may either be entered as text on the spreadsheet using the Python lambda format, or may be the name of any accessible Python function. In the example above func2 and func3 are included in the pyScipy3 module:

def func2(x):

return -2*x**4 + 2*x**3 + -16*x**2 + -60*x + 100

def func3(x, a, b):

return -2*x**4 + 2*x**3 + -16*x**2 + -a*x + b

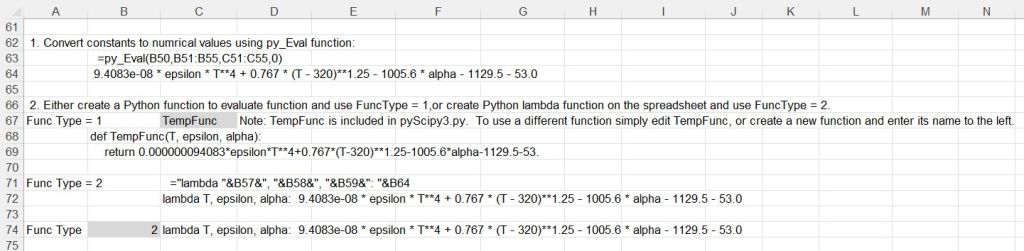

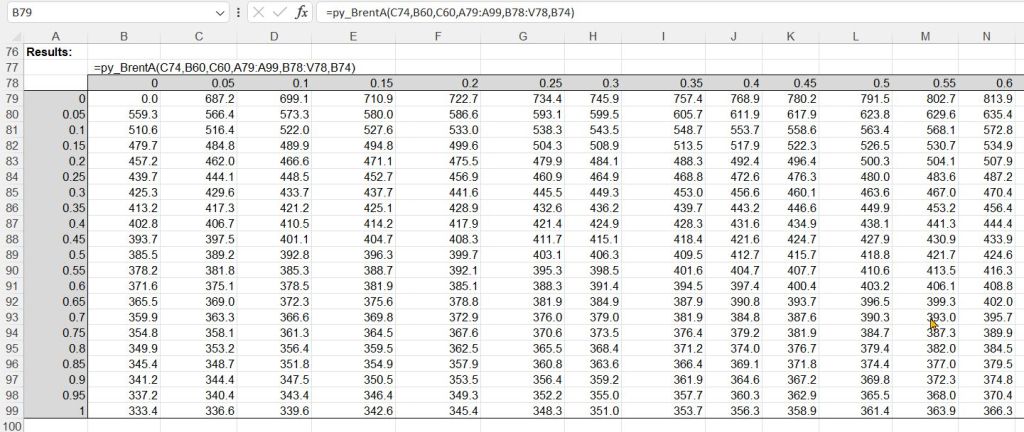

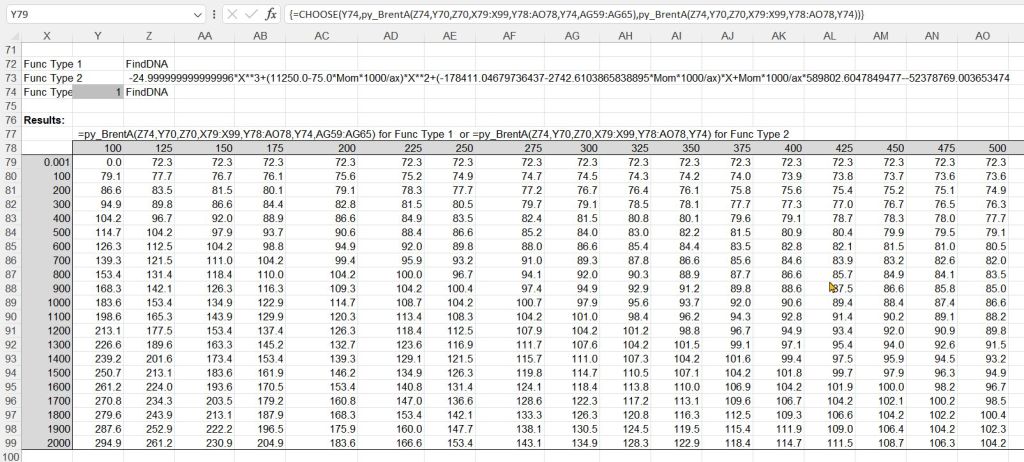

The py_BrentA function allows two of the function arguments to be transferred as row and column arrays, with the result returned as a table:

In the first example the function has one unknown, T, two variable arguments, epsilon and alpha, and five fixed arguments, G_1 to G_5.

The 5 fixed arguments have been converted to numerical values using the py_Eval function so that the unknown and the two variable arguments are the only arguments required for the py_BrentA function:

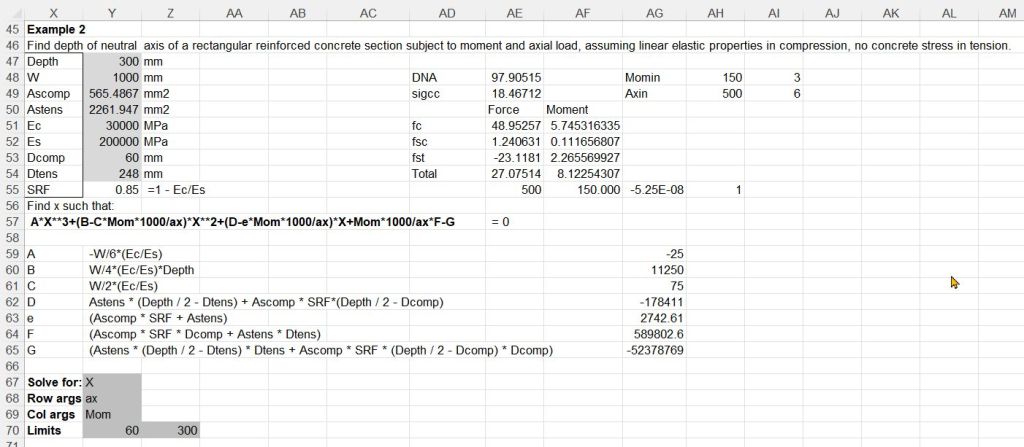

The second example finds the depth of the Neutral Axis of a reinforced concrete section with elastic properties with two variable arguments (applied axial force and bending moment) and 7 fixed arguments

For the on-sheet lambda function the fixed arguments must be converted to numerical values, again using py_Eval, but for the Python function the values can be passed to the function as an array:

def FindDNA(x, Ax, Mom, addargs):

A = addargs[0]

B = addargs[1]

C = addargs[2]

D = addargs[3]

E = addargs[4]

F = addargs[5]

G = addargs[6]

ecc = Mom*1000/Ax

return A*x**3+(B-C*ecc)*x**2+(D-ecc*E)*x+Mom*1000/Ax*F-G

On the spreadsheet either approach may be used by entering 1 or 2 in the “Func Type” cell (Y74).

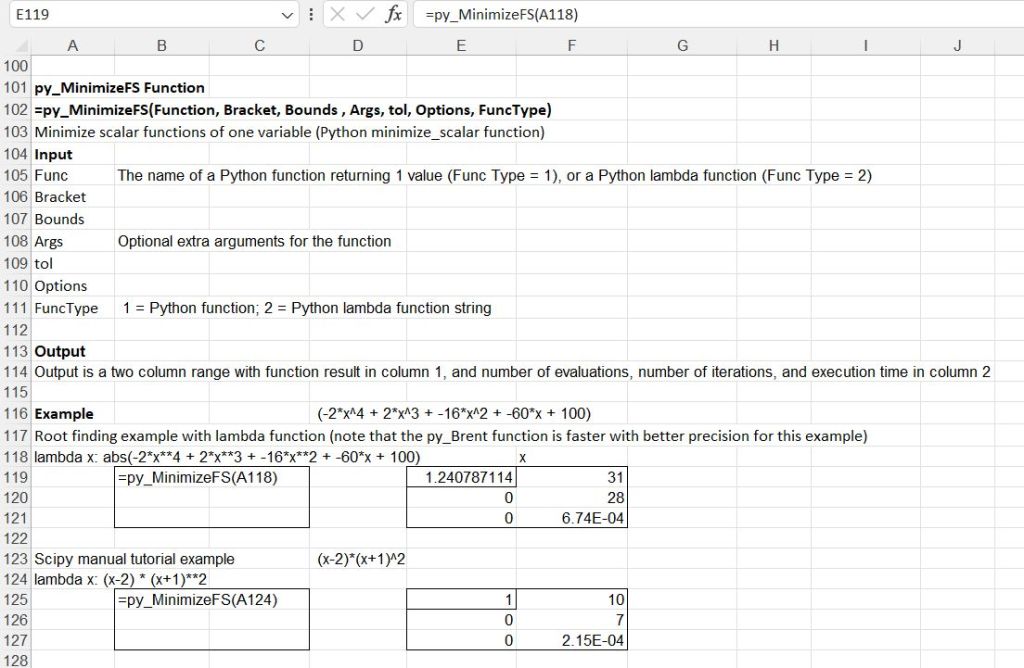

The py_MinimizeFS function has similar functionality to py_Brent, but uses the Python minimize_scalar function, that allows alternative solver methods:

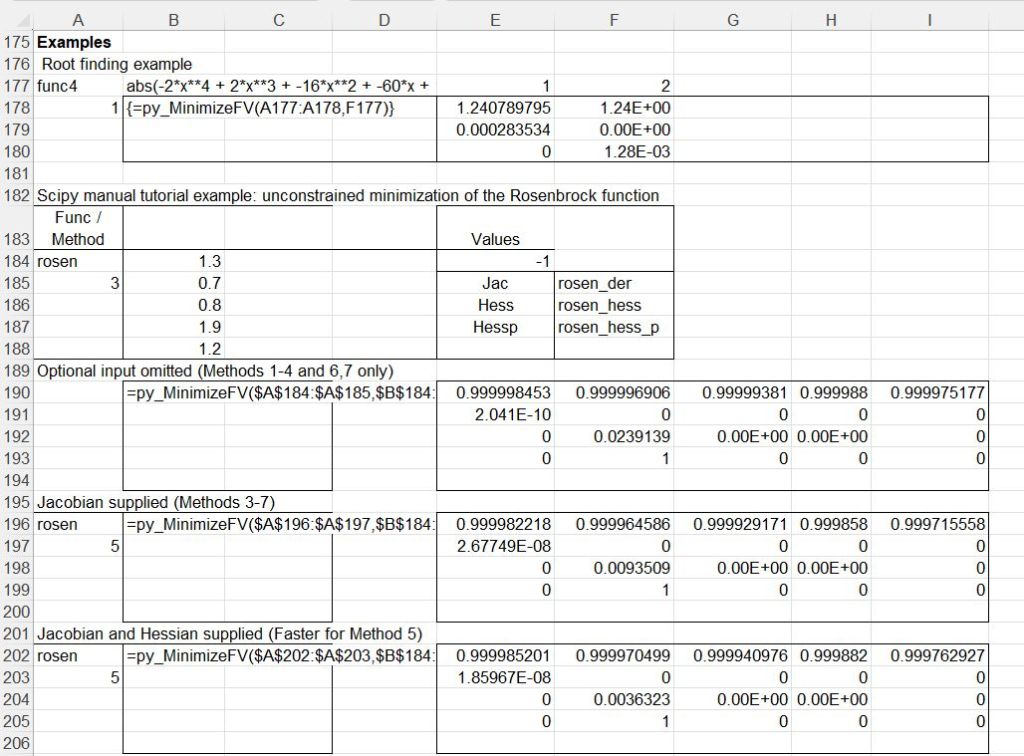

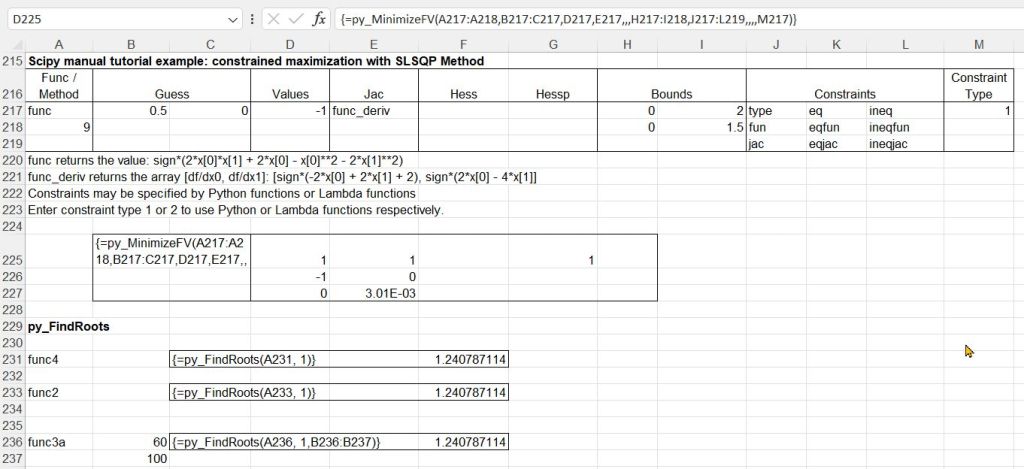

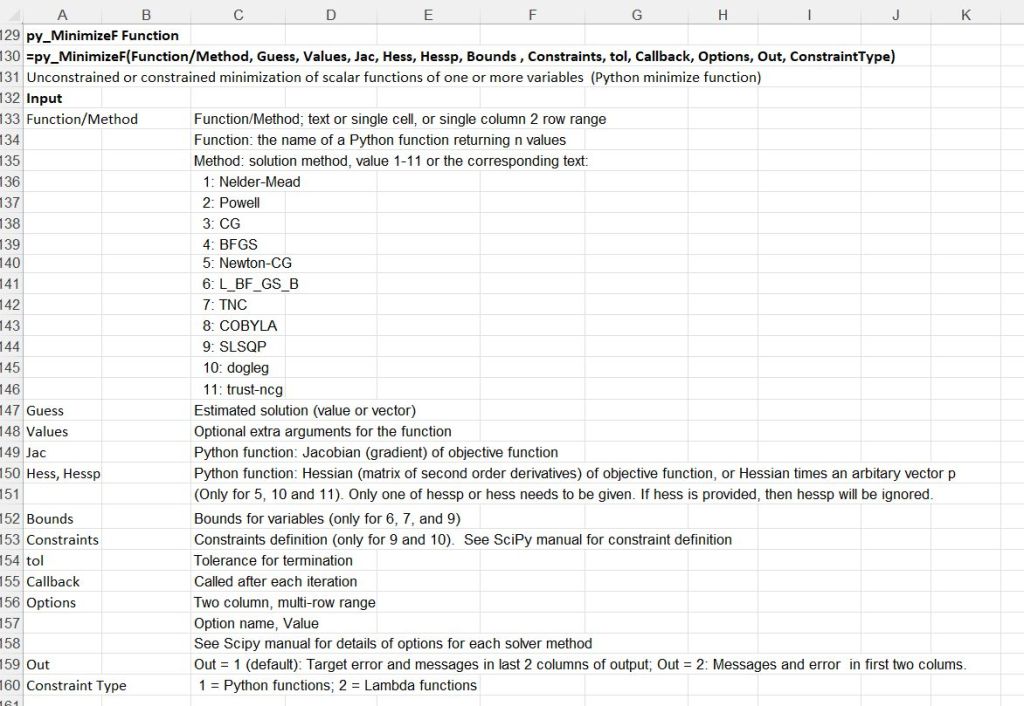

The py_MinimizeF function provides unconstrained or constrained minimization of scalar functions of one or more variables using the Python minimize function, using 11 alternative solver methods.

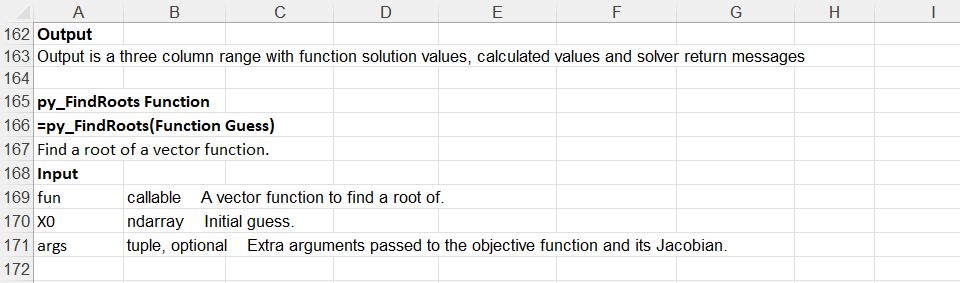

The py_FindRoots function returns a root of a vector function.

Examples in the spreadsheet include the root finding example used for the py_Brent function, and more complex examples from the Scipy documentation: