This post was prompted by a question at the Eng-Tips forum:

which asked why Mathcad was generating LU matrices different to those calculated from the basic theory. The short answer was that there is more than one way to do LU decomposition. This post looks at the question in more detail, including examples of the basic procedures, and how and why the variations are used.

LU decomposition is an efficient method for solving systems of linear equations of the form Ax = b, where A is a square matrix and b is a vector. A is decomposed into a lower triangular matrix, L, and an Upper triangular matrix, U, such that LU = A. It is then a simple process to find the vector x such that LUx = b, for any values of b, without having to repeat the decomposition process.

Many of the on-line articles on the procedures for decomposition (including Wikipedia) are very hard to follow, but I found a clear and comprehensive tutorial at:

LU Decomposition for Solving Linear Equations

The code listed at the end of this post is a modified version of code at the link above.

The basic process to find x such that Ax = b is:

- Decompose the matrix A into a lower triangle, L, with a leading diagonal of 1s, and an upper triangle, U.

- Use forward substitution to find y such that Ly = b

- Use backward substitution to find x such that Ux = y

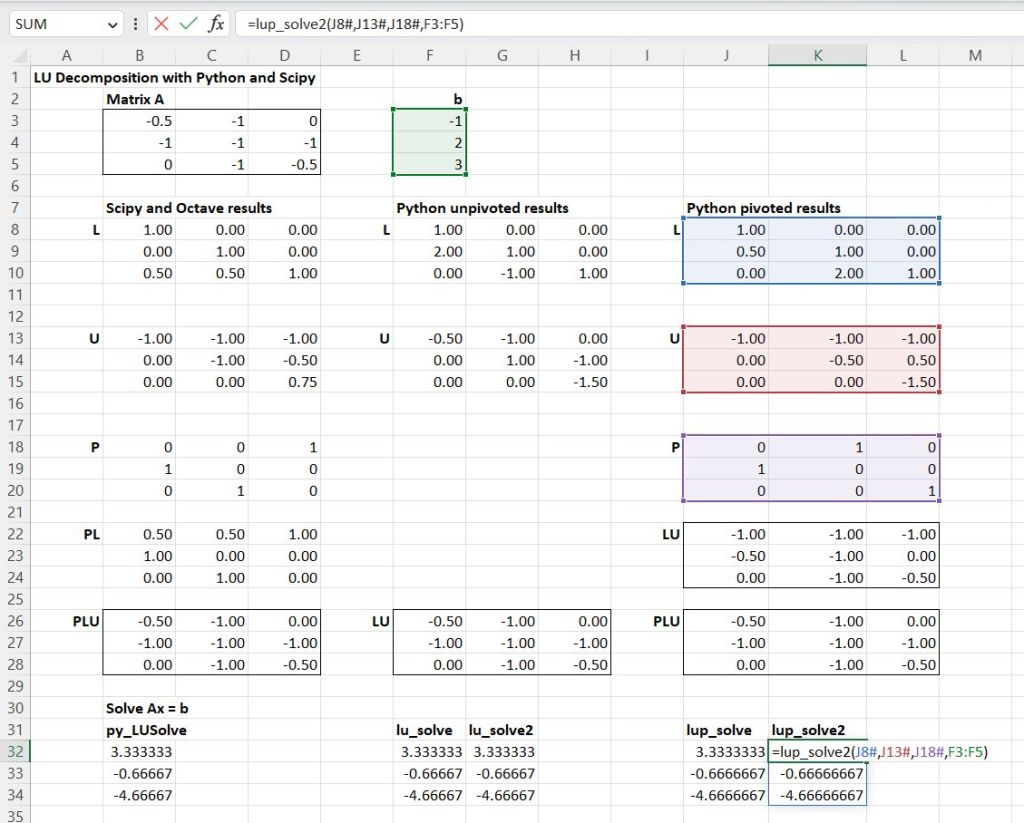

Python code for this procedure is shown below. Applying this procedure to a 3×3 matrix gives the results shown in the screenshot below, under Python unpivoted results:

- Triangular matrices L and U are generated from Matrix A.

- Multiplying L by U gives LU which is equal to A.

- The lu_solve function follows the full process to generate the solution with A and b as input.

- The lu_solve2 function has L, U, and b as input, and returns the same result.

- The Scipy function LUSolve returns the same results, but the Scipy decomposition functions generate additional P (pivot) and PL matrices. (Octave returns the same results).

The reason for the introduction of the additional matrices can be seen in the screenshot below:

The top left value of the Matrix A has been changed to zero. The calculation of the unpivoted L matrix now requires a division by zero, giving invalid results. The pivoting process moves the matrix rows and/or columns to avoid the zero at the top left, and remove the division by zero.

There are alternative methods of pivoting, as can be seen in the Scipy and Python pivoted results above, but both result in a PLU matrix identical to the original Matrix A, and the same results. Python code for the whole decomposition and solving process is shown below, without and with pivoting.

Without pivoting

Decompose Matrix A to Lower and Upper triangular matrices:

def lu_decomp(A):

"""(L, U) = lu_decomp(A) is the LU decomposition A = L U

A is any matrix

L will be a lower-triangular matrix with 1 on the diagonal, the same shape as A

U will be an upper-triangular matrix, the same shape as A

"""

n = A.shape[0]

if n == 1:

L = np.array([[1]])

U = A.copy()

return (L, U)

A11 = A[0,0]

A12 = A[0,1:]

A21 = A[1:,0]

A22 = A[1:,1:]

L11 = 1

U11 = A11

L12 = np.zeros(n-1)

U12 = A12.copy()

L21 = A21.copy() / U11

U21 = np.zeros(n-1)

S22 = A22 - np.outer(L21, U12)

(L22, U22) = lu_decomp(S22)

L = np.zeros((n,n))

U = np.zeros((n,n))

L[0,0] = L11

L[0,1:] = L12

L[1:,0] = L21

L[1:,1:] = L22

U[0,0] = U11

U[0,1:] = U12

U[1:,0] = U21

U[1:,1:] = U22

return (L, U)Find y such that Ly = b

def forward_sub(L, b):

"""y = forward_sub(L, b) is the solution to L y = b

L must be a lower-triangular matrix

b must be a vector of the same leading dimension as L

"""

n = L.shape[0]

y = np.zeros(n)

for i in range(n):

tmp = b[i]

for j in range(i):

tmp -= L[i,j] * y[j]

y[i] = tmp / L[i,i]

return yFind x such that Ux = y

def back_sub(U, y):

"""x = back_sub(U, y) is the solution to U x = y

U must be an upper-triangular matrix

y must be a vector of the same leading dimension as U

"""

n = U.shape[0]

x = np.zeros(n)

for i in range(n-1, -1, -1):

tmp = y[i]

for j in range(i+1, n):

tmp -= U[i,j] * x[j]

x[i] = tmp / U[i,i]

return xCombine the process to solve Ax = b

def lu_solve(A, b):

"""x = lu_solve(A, b) is the solution to A x = b

A must be a square matrix

b must be a vector of the same leading dimension as L

"""

L, U = lu_decomp(A)

y = forward_sub(L, b)

x = back_sub(U, y)

return xWith pivoting

Form pivot matrix, and pivoted L and U matrices

def lup_decomp(A, out = 0):

"""(L, U, P) = lup_decomp(A) is the LUP decomposition P A = L U

A is any matrix

L will be a lower-triangular matrix with 1 on the diagonal, the same shape as A

U will be an upper-triangular matrix, the same shape as A

P will be a permutation matrix, the same shape as A

"""

n = A.shape[0]

if n == 1:

L = np.array([[1]])

U = A.copy()

P = np.array([[1]])

return (L, U, P)

# Form pivot matrix, P

P = np.identity(n, dtype = np.int)

A_bar = np.copy(A)

for row in range(0, n):

i = np.abs(A_bar[row:,row]).argmax()

if i > 0:

temp = A_bar[row+i,:].copy()

A_bar[row+1:row+i+1,:] = A_bar[row:row+i,:].copy()

A_bar[row,:] = temp

temp = P[row+i,:].copy()

P[row+1:row+i+1,:] = P[row:row+i,:].copy()

P[row,:] = temp

if out == 3: return P

if out == 4: return A_bar

(L, U) = lu_decomp(A_bar)

if out == 5: return L

if out == 6: return U

return (L, U, P)Solve by forward and back substitution:

def lup_solve(A, b):

"""x = lup_solve(A, b) is the solution to A x = P b

A square matrix to be solved

b must be a vector of the same leading dimension as A

"""

L, U, P = lup_decomp(A)

z = np.dot(P, b)

y = forward_sub(L, z)

x = back_sub(U, y)

return xFull code to link the Scipy linear algebra functions, and the code above, to Excel via pyxll will be posted in the near future.